… And the tragic story of one American boy

Summer of 1994. The potting shed of an otherwise unassuming house gives off the vivid, infamous glow of radiation. Of the area’s 40,000 residents only one woman notices the unnerving wash of light coming from the shed. A foggy glow set against the dark Michigan night. But that woman doesn’t know what’s causing the glow, nor does she suspect that the radiation levels are starting to get so out of control that a Geiger counter has begun detecting higher and higher levels of radiation farther and farther from the house. The radiation is strong enough to seep through concrete. What was meant to be a sustained nuclear reaction is getting out of control, and it will soon mean the involvement of government officials and the establishment of a new “Superfund” site — an area claimed by the Environmental Protection Agency to be among the nation’s most contaminated land.

Shown above is the BN-800 breeder reactor in Russia.

The story really begins when David Hahn, the boy responsible for the nuclear contamination, receives his first chemistry book at the age of ten. The book outlines how to set up a laboratory and conduct simple experiments, allowing David to make harmless substances like alcohol. In this way chemistry truly becomes an art. Just as some children use painting or dance as a means of coping with their problems, so too did chemistry become a way for David to escape his life.

Throughout the years this romance with chemistry continues, growing more intricate as time goes by. At age 12 David has gone on to read college textbooks. At the age of 14 he’s surrounded himself with beakers of various shapes and sizes, some housing substances as explosive as nitroglycerin. In fact an explosion does take place. It happens when David is working with red phosphorus, a chemical that’s controlled by the DEA because it can be used for the manufacture of illegal drugs. This red phosphorus can be found on the striking surface of matchboxes.

But the real turning point comes when David gets one ambitious new goal: to build a nuclear reactor in his backyard.

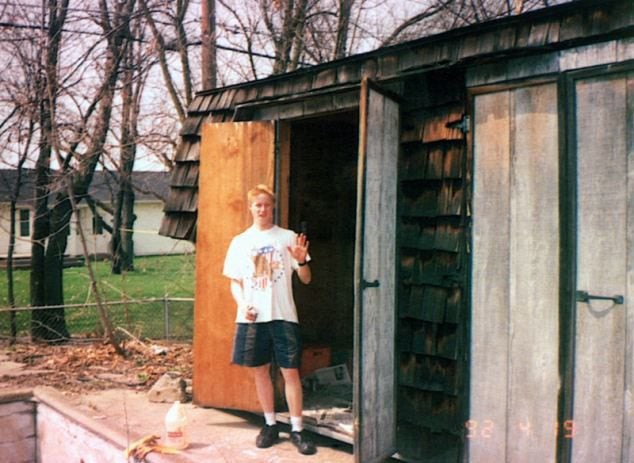

David stands outside his shed where a number of different experiments are underway at the same time.

It wasn’t going to be a conventional reactor. The specific kind of reactor David wanted to build was a “breeder” reactor. The United States had harbored hope for this kind of nuclear power in the 1960’s but, after multiple failures and extremely high costs, breeder reactor experiments had shut down by the 1980’s. The idea of breeder reactors itself sounds too good to be true. They produce more fissile materials — uranium or plutonium — than they consume. They are essentially self-replenishing.

Obtaining the tightly-controlled materials needed to build the reactor took years — years of being clever and years of being deceptive. While posing as a professor David contacted agencies like the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) who gave him instructions for building a neutron gun. Neutrons are used to irradiate materials, making them more fissionable and thus more valuable to his reactor. The NRC also provided contact information for suppliers of uranium. Among the materials he needed to acquire were things like americium-241, radium-226, uranium-235, uranium-238, and thorium-232. Some were easier to obtain than others.

A neutron gun, used to make materials radioactive, can be constructed out of lead and the americium within smoke detectors. Image by Robert Eagle.

Americium-241 is still used to this day within smoke detectors. It’s wrapped up tight under layers of foil and ceramic but it can be collected, as David did, by diligently scraping it out of hundreds of broken smoke detectors. He bought these from a company while claiming that it was for a school project. Once the americium was packed into a hollow lead container, its decay would produce neutrons. Thus he had built his very own neutron gun. The neutron gun was later converted into a more powerful radium gun that would produce even more neutrons. To gather the radium David visited antique shops and junkyards, looking for old clock faces which could have been decorated with radium paint. He chipped this radium paint off into vials and was able to purify them by mixing the radium paint with barium sulfate.

He went on in this way, stealing, lying, and patiently acquiring the materials in any way he could. The thorium he gathered from gas lanterns and heated it together with lithium to purify it. The beryllium he had a friend steal from the local college. Tritium he collected from glow-in-the-dark gun and bow sights. And so on and so forth until only one crucial component for his nuclear reactor was left: the core.

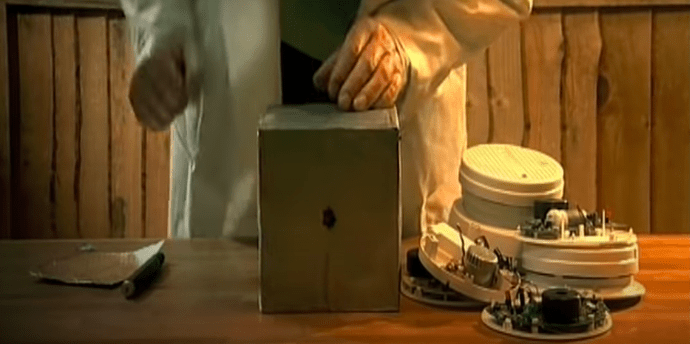

The americium and radium are placed together within a sheet of aluminum foil. On the right is seen the finished product: a reactor held together by duct tape and capable of making plutonium. Images by Robert Eagle.

Achieving a sustained chain reaction in his reactor was going to require at least 30 pounds of enriched uranium. In lieu of this David made a makeshift core out of the americium and radium he had used for his neutron guns. He mixed these with filings of beryllium and aluminum and then wrapped the new compound in more aluminum foil. This brimming, dangerous ball was surrounded by carefully constructed cubes of thorium ash, uranium powder, and carbon cubes wrapped in more foil. And all of this was secured in place by nothing other than duct tape. It was at this point, after the assembly of his core, that the situation began to escalate out of control.

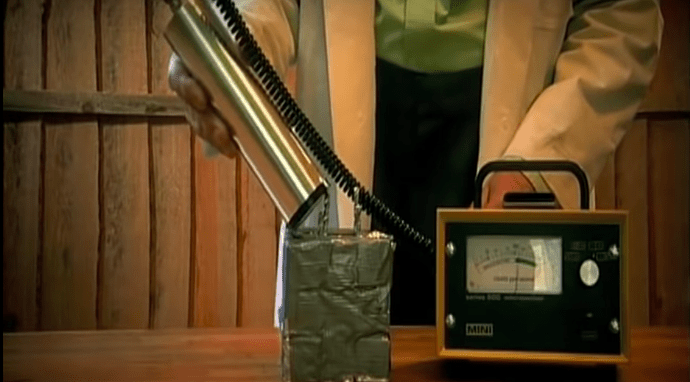

A few weeks later David’s Geiger counter noted a significant rise in radiation. There were nuclear reactions taking place within his homemade breeder, possibly even the creation of new plutonium. Regulating these reactions meant using control rods similar to those used at real nuclear power plants. The controls rods in this case were cobalt drill bits bought at a local hardware store and inserted into the space between the thorium and uranium cubes. The cobalt was absorbing the neutrons, but it wasn’t enough. The radiation levels still continued to increase until David was sent into a panic. It was clear that the more time passed the more he and the entire surrounding area were entering dangerous territory.

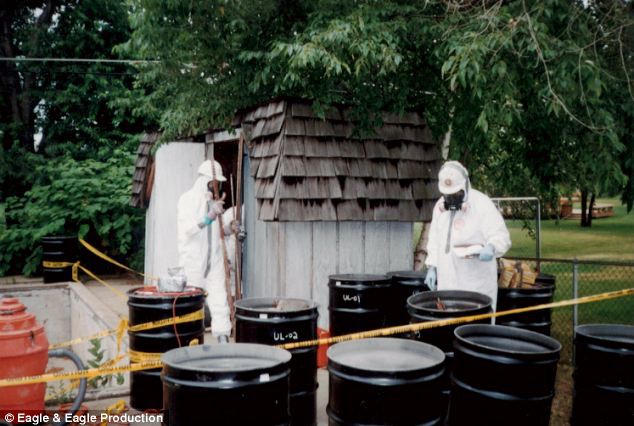

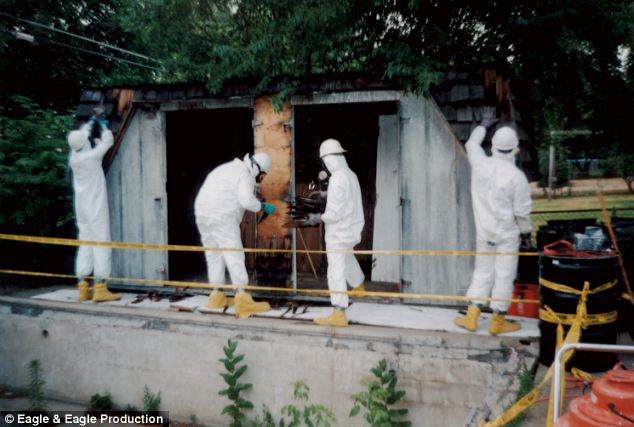

So it was that his breeder was dismantled and stuffed into shoeboxes, toolboxes, and the trunk of his car. He was eventually investigated by the police where he warned them that the toolbox was filled with radioactive materials. A bomb squad examined the toolbox, and the situation soon involved everyone from the EPA to the FBI and the NRC. November of that year saw radiological experts arrive at David’s home, picking through the contaminated materials and assessing how much radiation was in the vicinity. Some materials had radiation levels as high as 1,000 times the average. But the true levels of radiation were probably even higher since by this time most dangerous materials — the radium, thorium, and neutron gun — had been disposed of by David’s family.

A visit from the EPA and $60,000 later, the once radioactive potting shed had been cleaned up and declared a Superfund site by officials. Though they had offered for David to undergo an examination at a nearby power plant, David refused to go for fear of what he might learn. An estimated 4,000 people had been exposed to an unsafe, likely carcinogenic level of radiation.

But perhaps the most tragic twist in this story comes here, at the end.

The cleanup crew from the EPA stuffs radioactive parts into ominous black barrels.

Though what David did was highly controversial, one cannot deny that his was a brilliant and passionate mind. We might have even come to know David Hahn’s name as that of a renowned scientist were it not for what happened next. Instead of being encouraged and supported by his parents and peers, David was pushed into the US armed forces where he did time in the Navy. At some point in his adulthood he began using drugs, eventually being arrested and then dying of an overdose just shy of 40 years old.

It’s difficult not to feel that there may have been some kind of connection to the dismantling of his breeder reactor all those years ago. That project had been, for David, a masterpiece of sorts. A work that held within it a huge part of himself. He did note that for a long time after that visit from the EPA he had fallen into a deep depression. It’s not a long shot to say that a lot more was taken apart that mid-90’s day than just a secretive little potting shed and the remains of a hopeful nuclear experiment.

https://ella-alderson.medium.com/how-to-build-a-nuclear-reactor-in-your-backyard-8ab8d7e2937b