https://i.imgur.com/MPNRI0Y.jpeg

Source: Pexels

Science is not a religion. The theory of gravity clearly does not exist on the same epistemological plane as the idea that the world is carried on the back of a giant turtle. Electricity is a much more satisfying explanation for thunder and lightning than a sexually-incontinent, toga-clad Greek superbeing trapped in an eternal midlife crisis. And, no matter how much wisdom may be contained in the Old Testament, it will not get you to the Moon.

Like other frameworks which are essential for civilised life, such as justice, science is a process — and not a result. It is a method of rational enquiry inherited from Enlightenment philosophy and steadily updated to suit modern contexts. Following this method allows the determination of new and useful truths about the universe.

The precise formulation of this scientific method resists comprehensive definition, but three features are essential: a hypothesis, or ‘educated guess’; testing of that hypothesis by a repeatable experiment that attempts to disprove the hypothesis; and determination of whether the hypothesis is true based on the evidence produced by the experiment.

This method is clearly no religion. In theory, the scientific method actually shares more in common with a computer program than a religious system, relying on lines of inflexible code to carry it from conjecture to truth. Yet the scientific method does not have the benefit of deterministic circuitry to execute its commands: its hardware is human beings.

This chink in the armour of science is beloved by Leftist scientific sceptics. “If science is done by white people,” they claim, “then it must surely be ‘white science!’” Perhaps black science would arrive at a completely different set of truths, and explain how the shaman calls the lightning. After all, science is just a subjective social construct — why wouldn’t black people construct it differently?

While the production of scientific knowledge is undoubtedly a social process, it is not an arbitrary social process. Black scientists, doing their job properly, would determine the same gravitational constant as scientists of any other race or species. Though the equations they use to interpret the world might be different in formulation, they would be entirely interchangeable with those we use today. Indeed, the social process of science might be radically different among alien scientists, but their scientific model of the universe would be quite familiar (if, perhaps, resistant to translation).

Thus, historical attempts to create ‘alternative sciences’ for ideological purposes have led to mass human tragedy. In the early Soviet Union, an agriculturalist named Trofim Lysenko came up with radical new theories of agriculture based not on natural science, but on Marxist-Leninist ideology. This resulted in his rapid rise through the Soviet hierarchy and the wide dissemination of his untested claims. Among such claims was the idea that small birds such as sparrows reduce grain output, and so should be exterminated. This misguided idea was tragically put into practice by armies of Communist Chinese peasants, who thronged across the countryside banging pots and pans to deny the sparrows anywhere to land until they dropped out of the sky from exhaustion. The results were catastrophic. The multitude of small insects and parasites kept in check by bird populations devoured their crops, creating an entirely preventable man-made famine in which tens of millions of people were killed .

Divergence from science on ideological grounds is clearly very dangerous. Science is much more precious and useful than an arbitrary social construct. Scientific knowledge is clearly not mere subjective opinion.

And yet, the argument that science is a belief system does not dissipate quite so easily. Even the most hardline science purist will agree that science is based on trust . We trust that science is conducted in good faith and published honestly. We trust that the accumulative knowledge of experts aligns with reality, even in fields where we lack the training to analyse their claims ourselves, or where we lack the time and resources to verify their conclusions through our own experiments. We trust that the equipment in our laboratory matches the stated specifications, and the samples and substances we acquire conform to what the label says. We can test some things, sure, but in order to get anywhere at all, there are many things which we must simply accept on trust.

Trust and faith are similar concepts. With faith, there is no consideration of prior experience: a thing is believed without any evidential foundation. Trust tends to be established through evaluation against past experience. Both faith and trust are types of belief, and we do not fundamentally differentiate between something believed through faith or through trust. Yet we humans do have an understanding of uncertainty, which reflects an advanced knowledge of the fallibility of our beliefs. Things about which we are certain are thought of as ‘knowledge’ while concepts that entertain uncertainty are described using words like faith, belief, or trust.

The result of science is that we form certainties. At some point, we lay down the tools of the process of science and emerge with the conviction that the Earth is round, or that evolution by natural selection is a manifest biological process, or that the cosmos originated in a ‘Big Bang’. To leave these questions open and live in a world of total uncertainty is to embrace insanity, and betray the very purpose of scientific enquiry — the determination of objective truths about the natural universe.

Once such a certainty has been formed, however, scientists behave just like any other human beings who have oriented themselves around a belief system. They create an in-group and an out-group, and the out-group becomes tainted with associations of naïveté, irrationality, idiocy, malevolence, or madness. Fraternising with such people is to invite accusations of ideological contagion, even if the purpose of such discussions is to bring scientific truth to the unenlightened masses.

The behaviour of science as an institution conforms to Kuhn’s model of knowledge paradigms. A paradigm is an intellectual framework shared by a community of researchers, and research activity is motivated by attempts to resolve anomalies (discrepancies between the knowledge of the current paradigm and reality). After a time, the number of anomalies accumulates to the extent that the paradigm itself must be radically altered, leading to a revolution whereby the established scientists are overthrown from their position of authority in favour of new scientists sharing a new intellectual framework. This is the famous ‘paradigm shift’ — and it is as much a social process as a scientific one.

Speaking of social processes, gatekeeping is an inherent part of institutional science. The masters of the dominant paradigm decide what is relevant out of the vast heap of material that is novel. Relevant material is incorporated into the dominant paradigm, whereas irrelevant material is dismissed. In the same way, contributing an idea to the heap of potential material cannot be done by anyone: you must have plenty of credentials — usually including a PhD — and be based within an institution that has the clout and finances to move your idea forward.

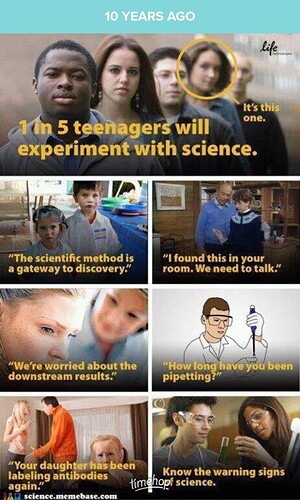

Given this reliance on trust and the use of science as a belief-forming tool, it is no surprise that many science adherents within the ‘I F***ing Love Science’ tradition attach the solemn certainties of scientific enquiry to utter pseudoscience. The process of science is hard. It requires years of dedication, hard thinking, and grind to master science, so why not skip straight to the conclusions? Even qualified scientific researchers are not immune to this lure. The road of true science is paved with easy shortcuts that must be rejected in order to retain the epistemic value of the endeavour, and this is presumably why science is described as a series of disciplines.

The problem, of course, is that science cultists end up orienting themselves around false beliefs with fanatical certainty. It is then imperative that discourse be controlled to preserve their beliefs. Science, in their minds, is not a process but a list of dogmas. Unbelievers are branded ‘anti-science’ simply for disagreement. Scientists who disagree with these dogmas are treated with the scorn and vitriol of a mediaeval apostate. The media and social media align themselves around the protection of false beliefs in the name of ‘Science’. This behaviour is very normal, very human, and very tribal — and it is this ‘Science’ which religious communities accurately identify as a religion.

In a tragic irony, the religious behaviour of science cultists has a stifling effect on real science. It also wields a corrupting power — many science cultists train up to become scientists while retaining their toxic conviction that the ends of science are more important than the process. Powerful, dogmatic institutions from the Catholic Church to the Soviet Union have stamped down on dissent for centuries, and the results have always been detrimental to rational enquiry in the pursuit of objective truth.

In conclusion, science appears to have many enemies, some of whom believe themselves to be its best friends. For those who are rightly sceptical of the annihilating potential of radical change, scientific advancement is easy to scapegoat as the source of all moral and social degradation. Yet we will never be rid of science: it has become our constant companion on this wild ride towards futurity, the formal incarnation of mankind’s innate curiosity. Science is a force that we must understand, and the price of good science is constant vigilance.