Gustave Zander and the 19th-Century Gym

As some of us squat, shove, and crunch our way toward new resolutions — while others arrive at the relieving conclusion that their Christmas kettlebell purchase makes for the perfect doorstop — we might wonder, with gratitude or suspicion, why and when gym going became such a widespread phenomenon. Long before Muscle Beach, tubs of whey protein powder, or the distinct grade of shame that emanates from an unused fitness club card, Dr. Gustaf Zander (1835–1920) was helping his pupils tone their pecs in his Stockholm Mechanico-Therapeutic Institute.

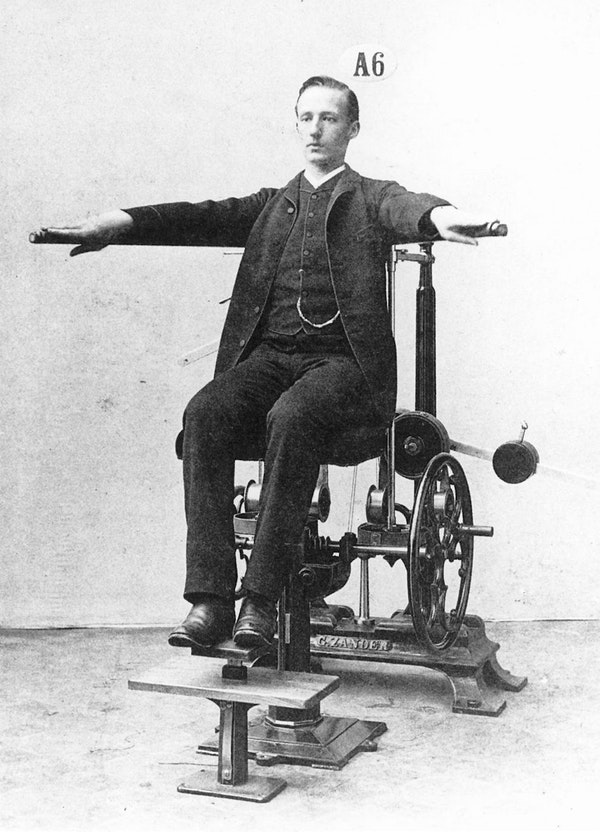

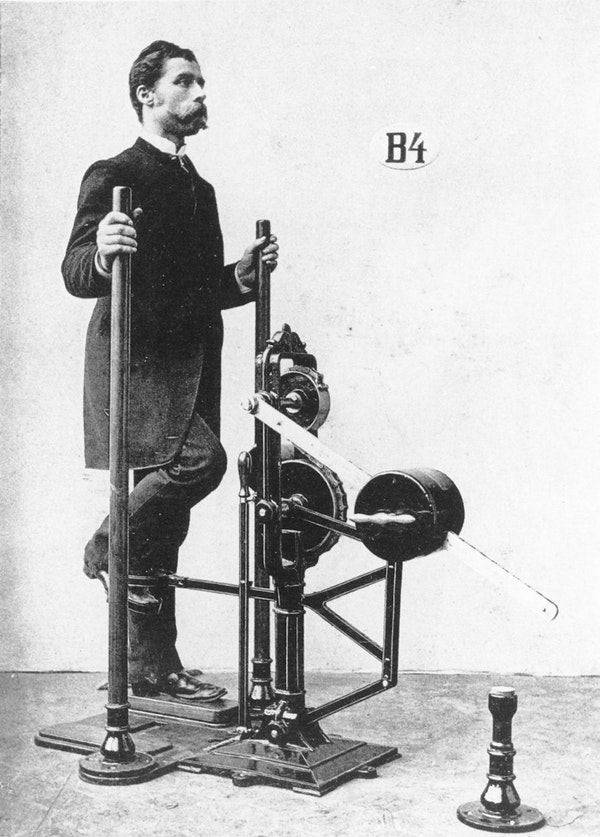

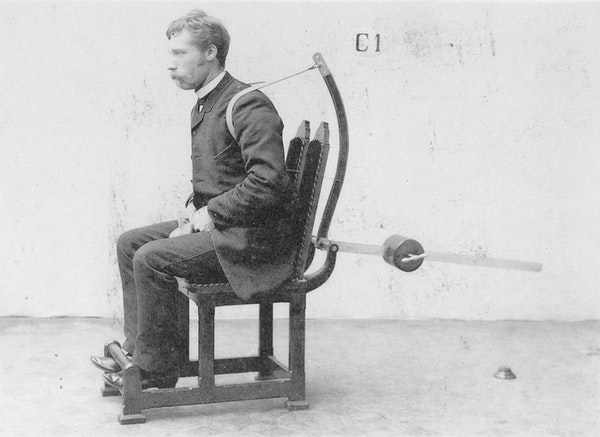

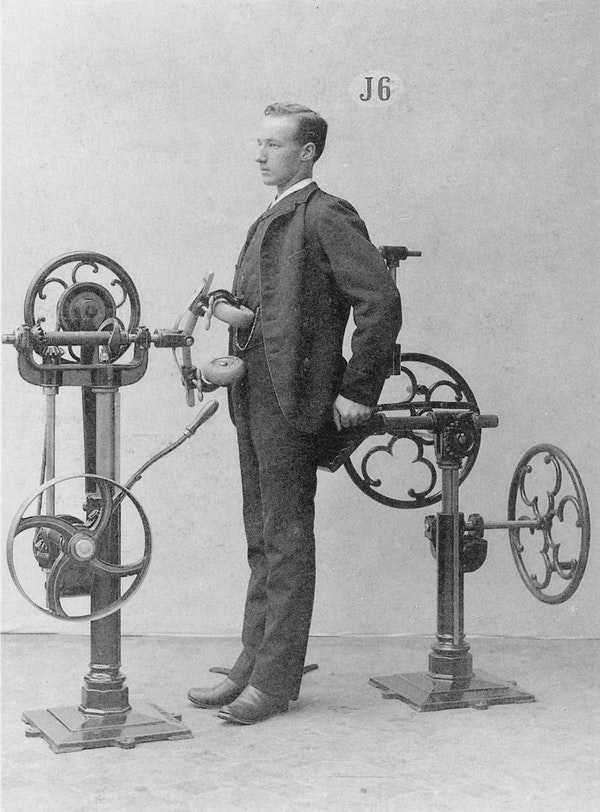

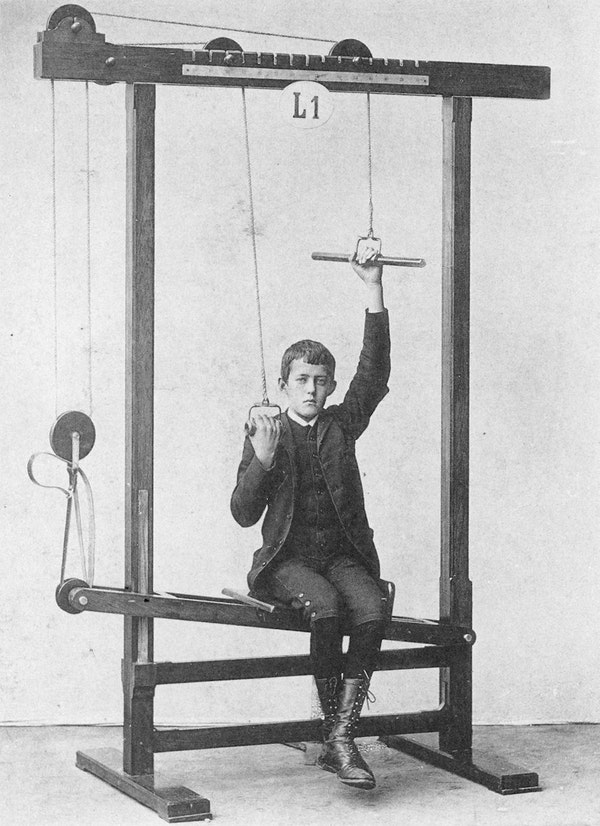

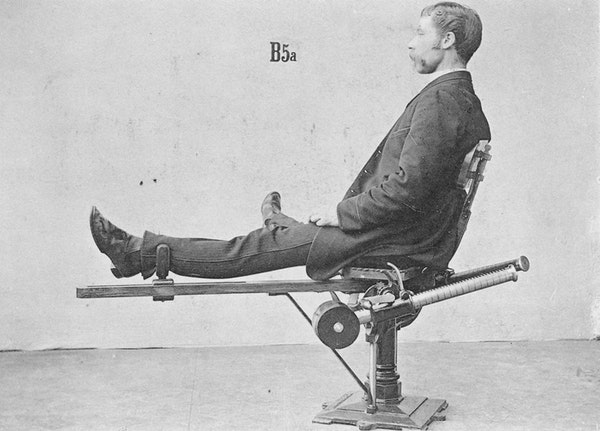

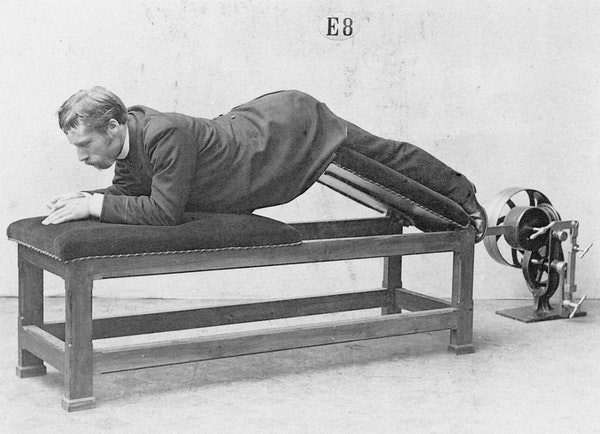

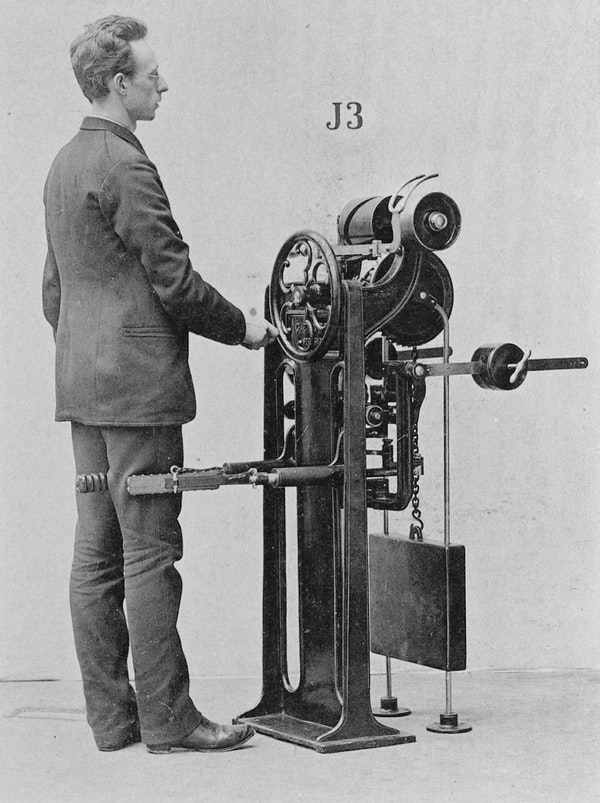

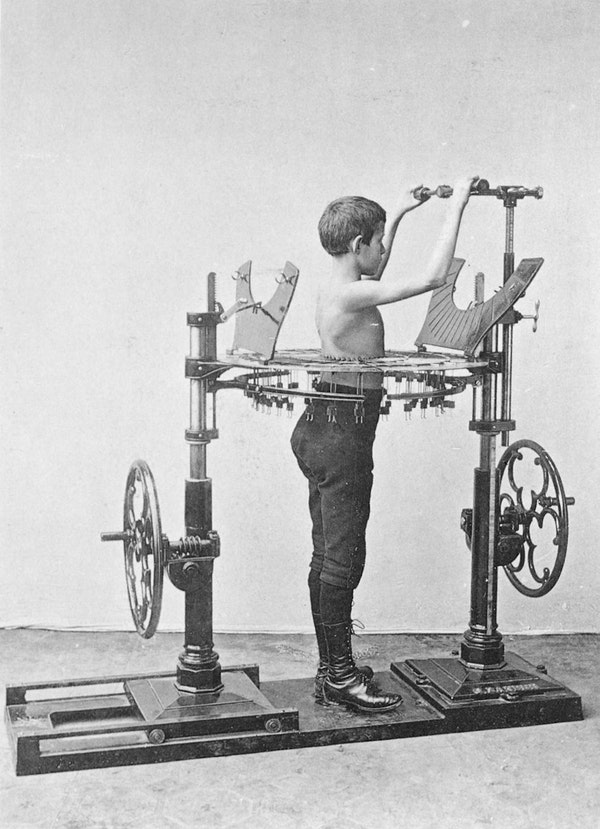

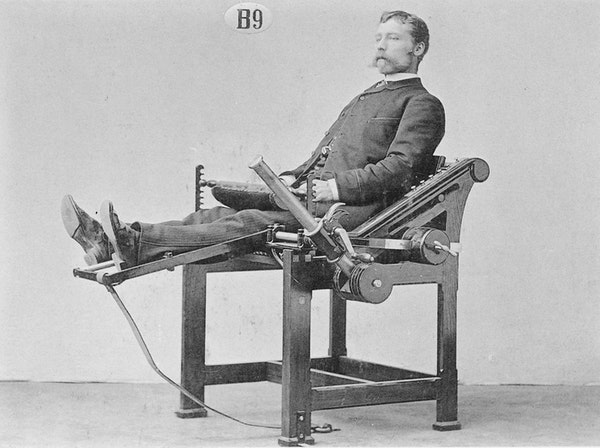

Of course, ritualized group fitness is nothing new: Ancient Greece had gymnasia ; the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) trained through the game now called lacrosse (one of many intersections between fitness and colonialism); and physical regimens have been encouraged or required by nearly every empire and religion in recorded history. Zander’s contribution and revolution came in the form of resistance training and muscle-group-isolating exercises using specialized machinery, precursors to those contemporary contraptions built from welded metal frames, rubber resistance bands, and stacking steel plates.

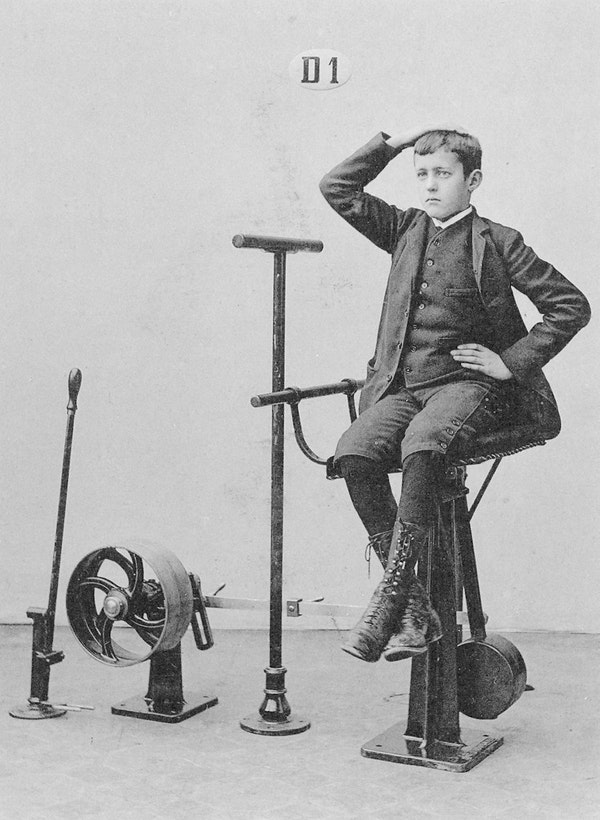

In his 1894 treatise on “medico-mechanical gymnastics”, Zander discusses his system as if administering a regimen of medication. “The prescription [of exercise] is methodically composed according to the needs and condition of the patient.” And the regimen worked. As Sven Lindqvist records, Zander’s success swelled at an anabolic rate. Having opened his first institute in 1865 with twenty-seven machines, by 1877 “there were fifty-three different Zander machines in five Swedish towns”. And not long after, Zander reinvented himself professionally. Once a lecturer in gymnastics at Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute, he soon became an international fitness entrepreneur, exporting equipment to Russia, England, Germany, and Argentina.

The history of the modern work out is inseparable from the history of work. In the late-nineteenth century, concerns related to occupational health and on-the-job injuries came to the fore during discussions among ergonomically-oriented physicians. Zander marketed his machines as safeguards against “a sedentary life and the seclusion of the office”, promising “increased well-being and capacity for work”. In a sense, his machines offset injuries caused by other machines: advances in mechanization created new forms of labor divorced from physical exertion. One had to work out to remain physically capable of performing further work in the office.

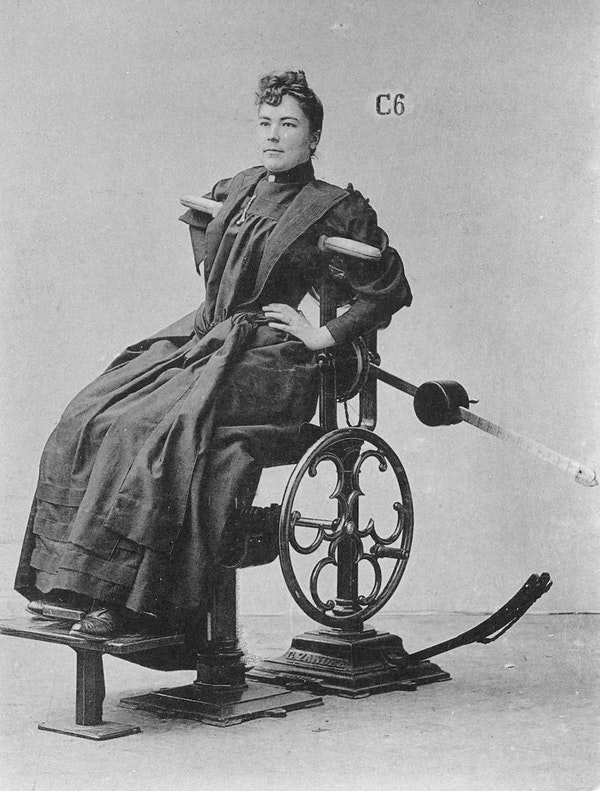

As Carolyn Thomas (formerly de la Peña) traces, in her history of “Cybex Space”, adapted from a larger project on machines and bodies, Zander’s project began under the auspices of Sweden’s welfare state. His research was government funded and the gyms accessible to all. After winning a design award at the 1876 Centennial and International Exposition in Philadelphia, he pivoted from a focus on general public “health” to furnishing “elite health spas” and private institutes with his “fitness” machines. “In mechanized workouts”, writes Thomas, “white-collar Americans pumped up their own superiority. By declaring that ‘fitness’ equaled a perfectly balanced physique, rather than the ability to perform actual physical tasks, body power was shifted from laborers to loungers.”

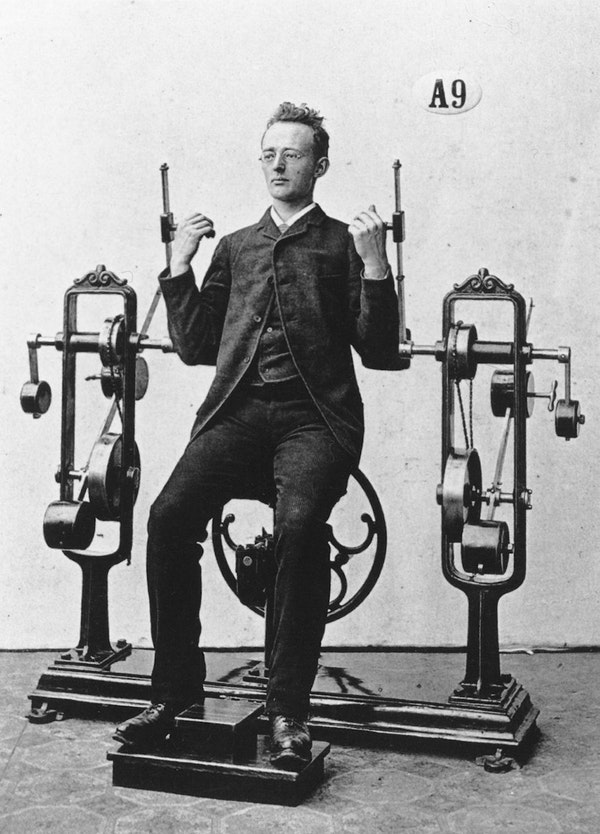

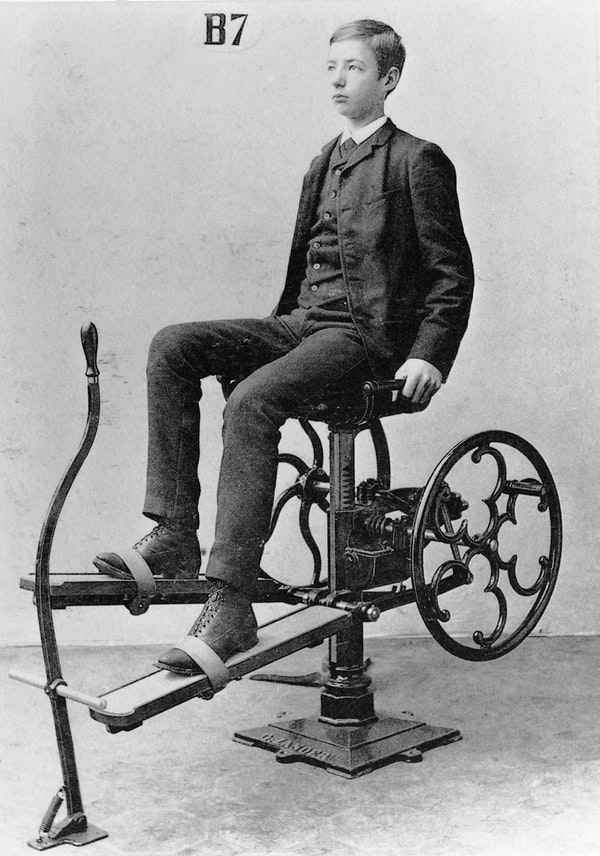

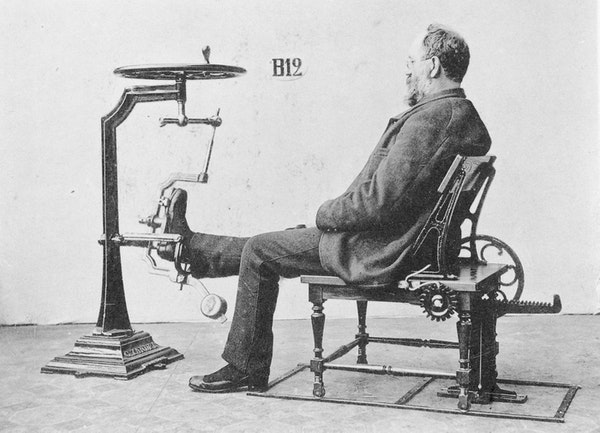

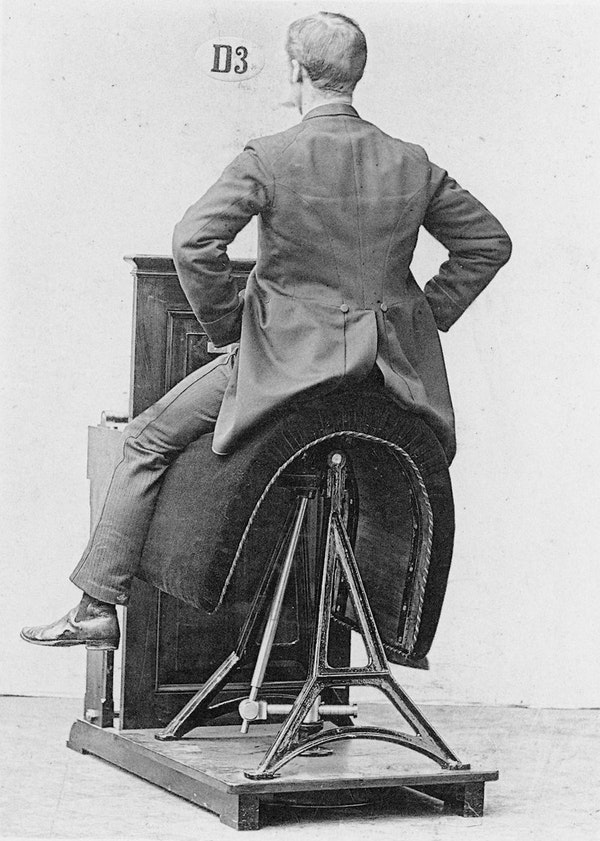

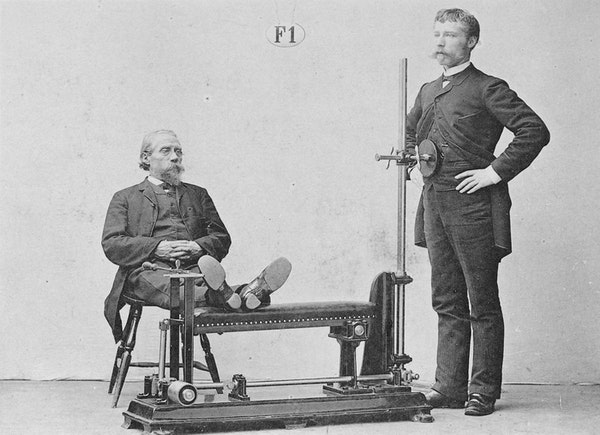

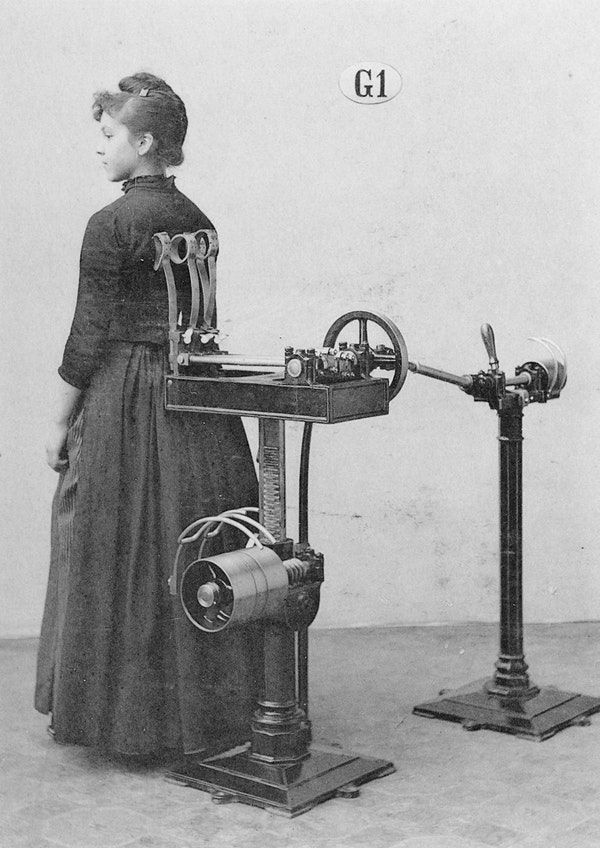

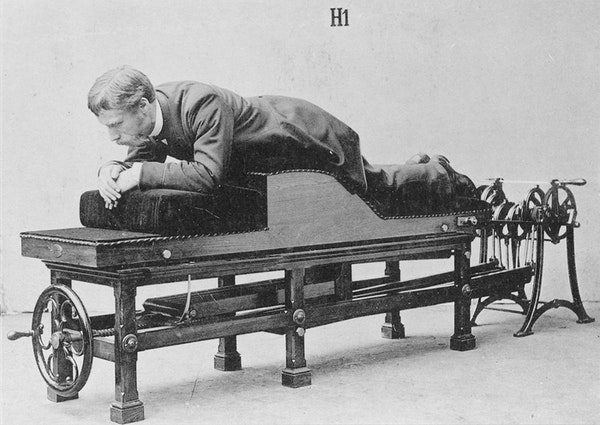

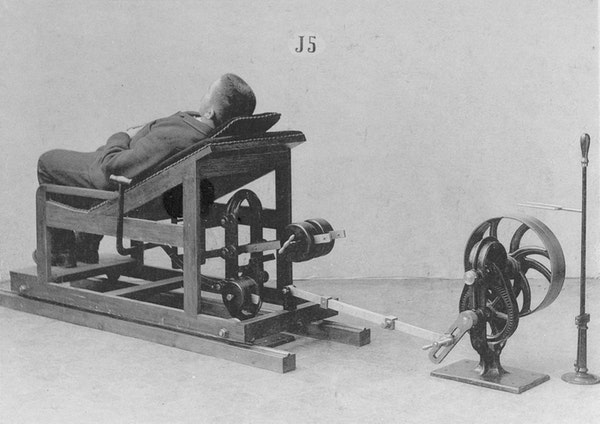

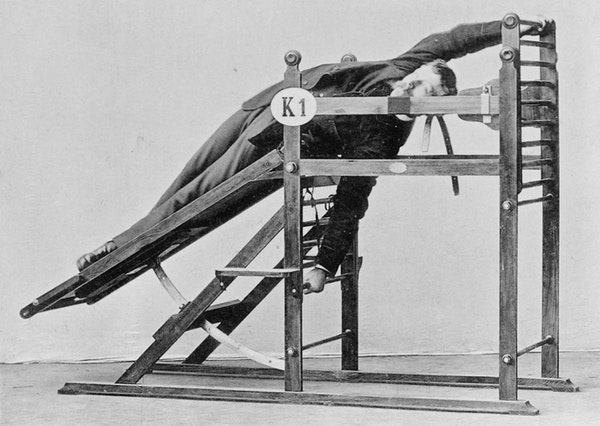

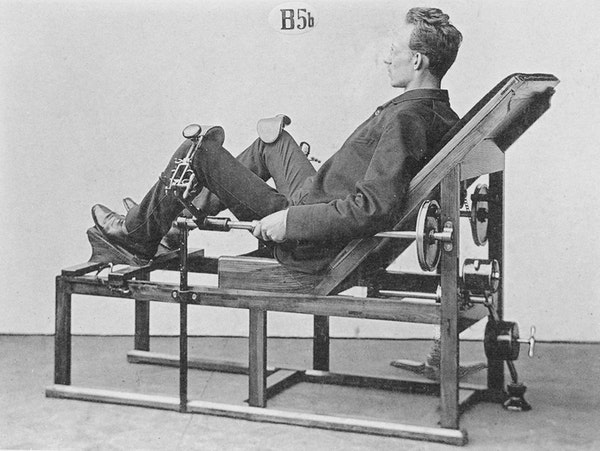

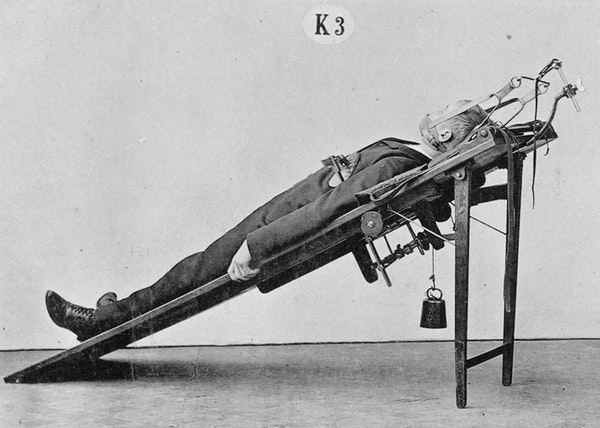

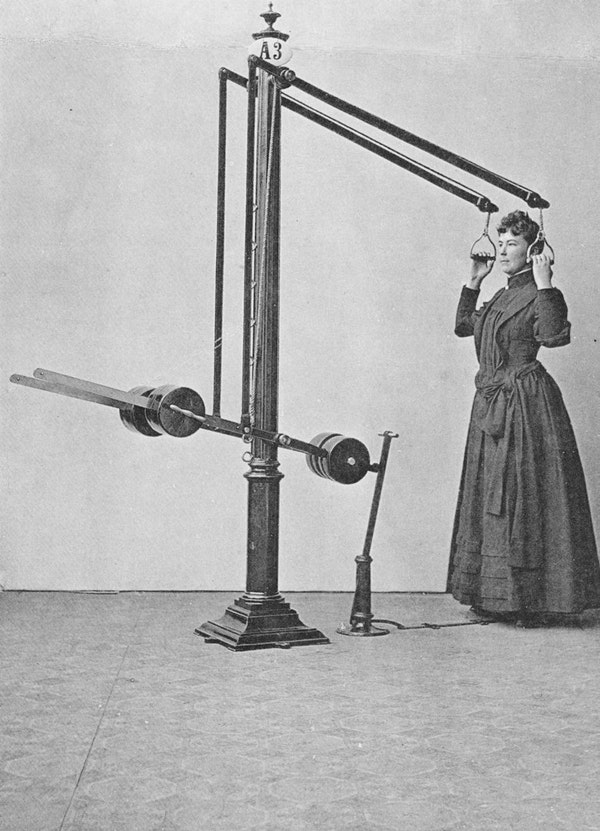

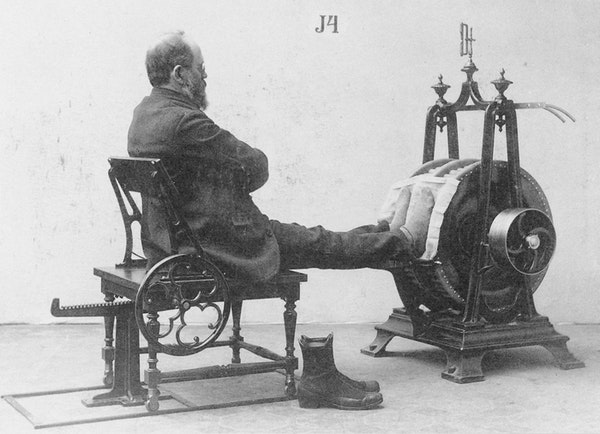

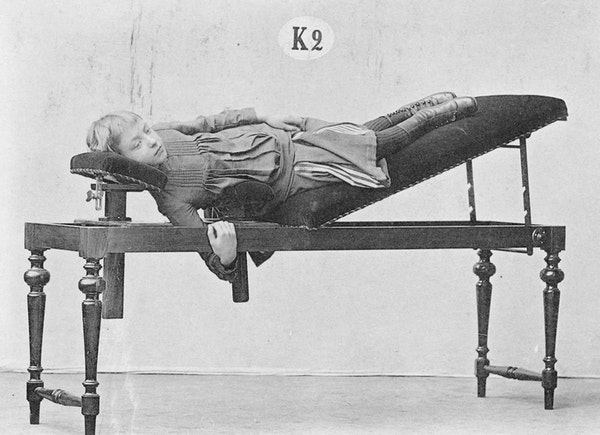

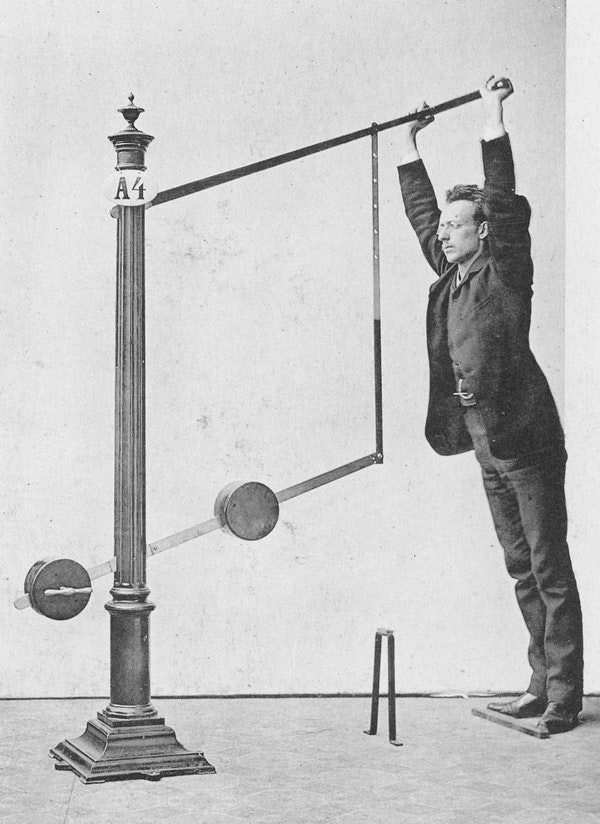

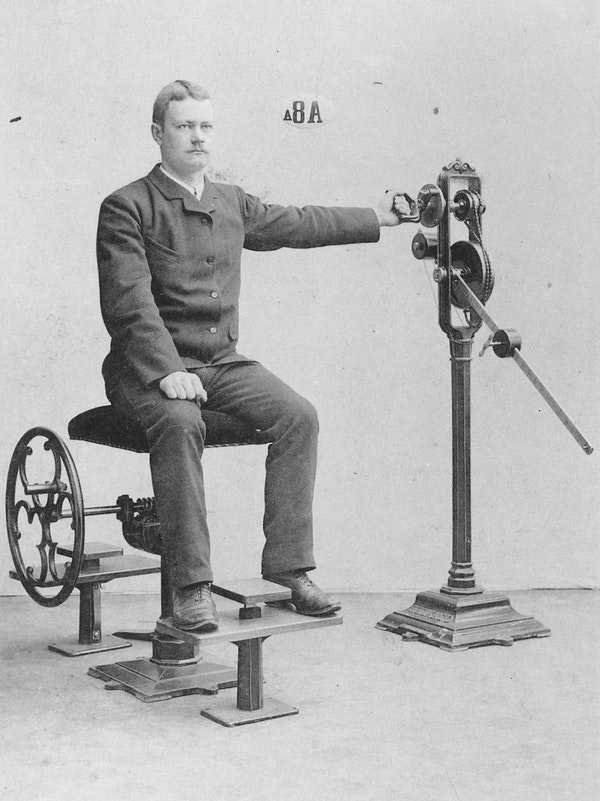

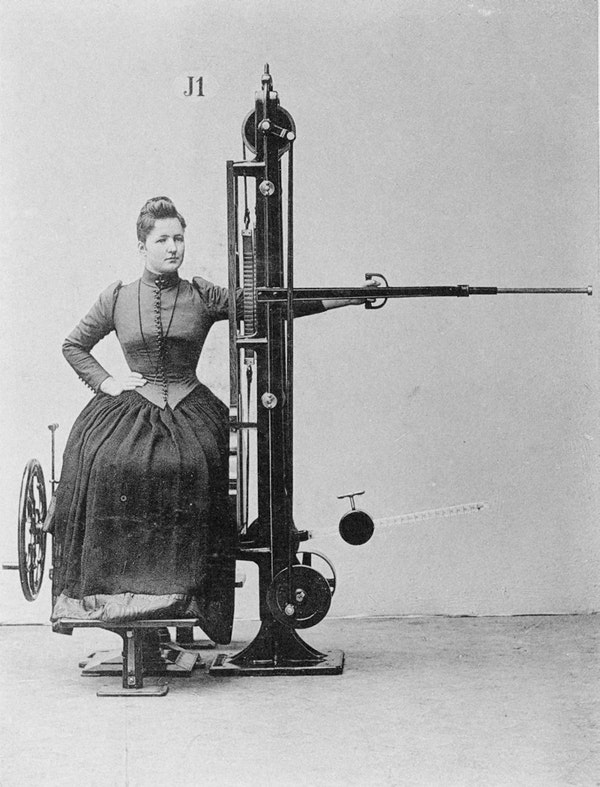

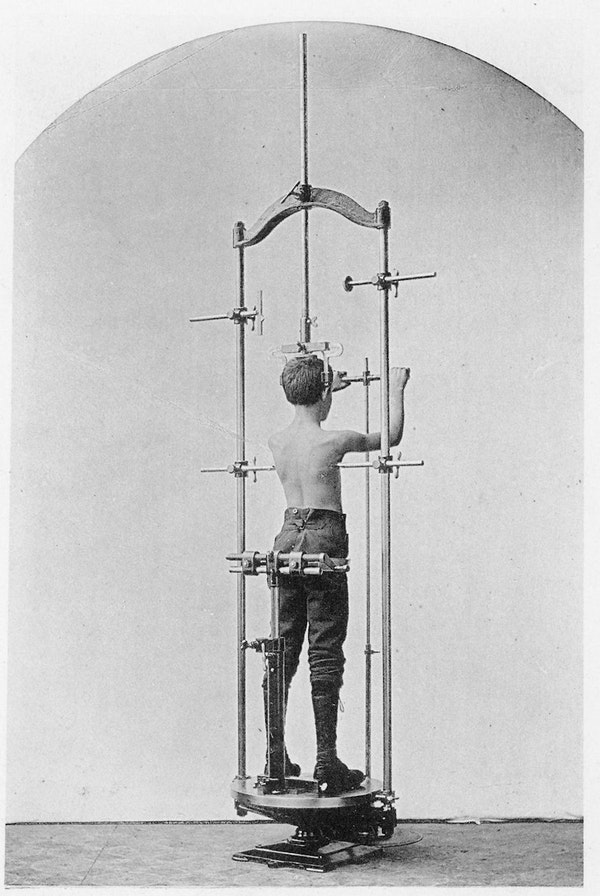

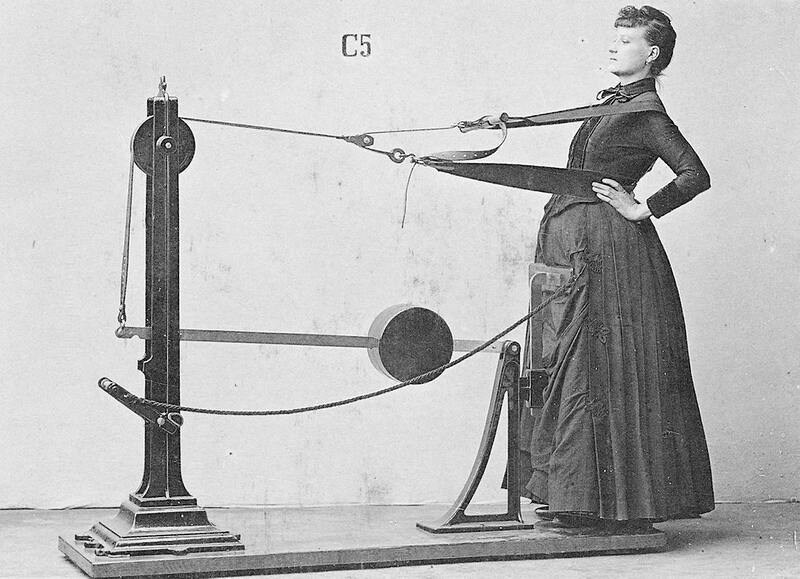

The images collected below come from a catalogue distributed by “Görransson’s mekaniska verkstad”, a gymnastics equipment company, and are reproduced in a book published by Dr. Alfred Levertin on Dr. G. Zander’s Medico-Mechanische Gymastik (1892). Aside from the shock of seeing the gymgoers’ choice of athletic wear (thick three-piece suits with pocket watches affixed on chains), there is something uncanny about the marked lack of exertion displayed on Zander’s patients’ faces. As Thomas explains, unlike contemporary Peloton and Crossfit leaderboards, which prioritize competition and reward individual effort, Zander’s technology was marketed as a passive activity — with some devices even driven by steam, gasoline, or electricity. All one had to do was connect their body to the machine and it would do the work for them. . . or so they were told.